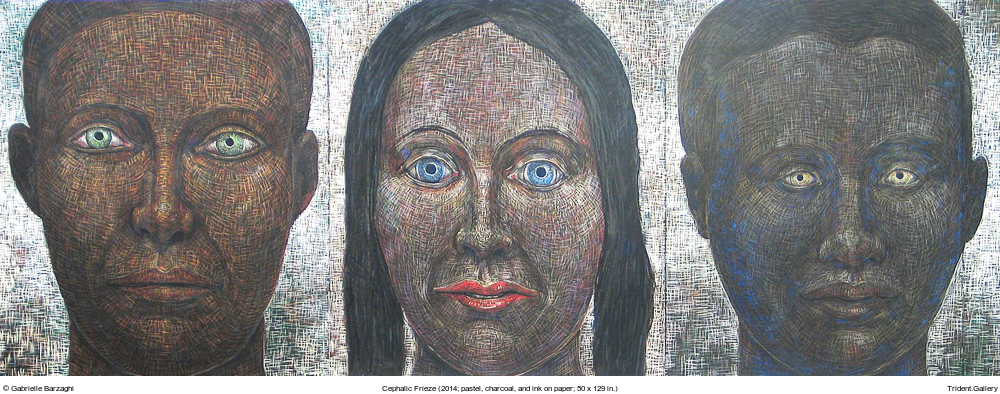

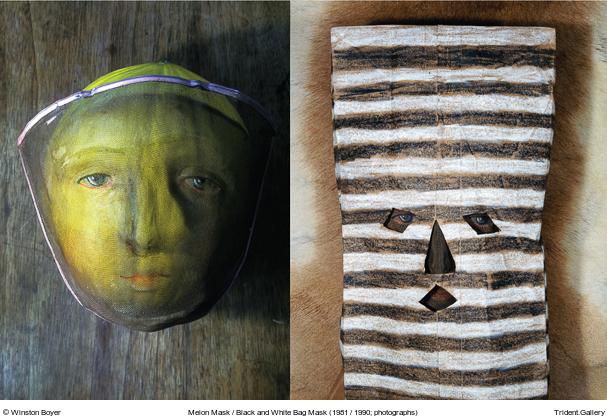

For more than 35 years, Winston Boyer has photographed a pair of painted screen-mesh masks to create a series of whimsical and profound still lifes called the Mask Series. Like Boyer’s work generally, images in the Mask Series are diverse, unpretentious, and painterly in composition, color, and texture. While curating The Political Body, I spent a lot of time with the Mask Series and gained a new appreciation for it. Two Mask Series images emerged for me as a powerful contribution to the exhibition.

The first was Black and White Bag Mask, an image strikingly exceptional within the series, because the familiar screen mask is barely visible. The boldly graphic rectangle and stripes contrast with the subtly variegated textures of the paper bag and the cowhide background, and the round, organic eyes of the mask are visible only through the crude geometry of the diamond cutouts of the bag.

The paper bag immediately suggests a familiar trope, a caricature of the impulse to hide one’s identity out of shame, and quickly becomes more serious as it recalls the act of hiding of one’s identity to avoid persecution or prosecution. As with most other uses of masks, these uses have a strong element of ritual, and even of overt symbolism: the executioner, the intruder, the terrorist, the Klansman. We are off to a promising start: the image conjures powerful emotions and meaningful circumstances involving bodily appearances and identity.

The bold black and white stripes deepen and complicate the idea of the concealment of identity. Are they a crude label imposed by the viewer on a more nuanced person within who is neither black nor white, the whole bag becoming an allegory of over-simplification? Or do they represent an attempt, like a zebra’s stripes, to confuse a predator’s vision and judgment? With reference to United States history, the stripes invoke black and white skin and the stripes of our flag. The doubling of masks—a mask on or for another mask—amplifies these questions and invites reflection on the variety of meanings and functions for masks.

The anxieties of Black and White Bag Mask are tempered by the fun and play of Melon Mask, which recalls the grotesques of the Old Masters and earlier medieval traditions. As I studied the Mask Series, I kept coming back to Melon Mask simply because I liked it, and before long, the patience and pretense for sustained attention that this enjoyment conferred on me began to pay a dividend. It is always a thrilling moment when a veil lifts and a work of art reveals itself, and at the same time promises further revelation.

Though there is much to say another time about the aesthetic beauty of this image, my genuine enjoyment of the Melon Mask is founded in the powerful sense of character it creates for me, which I perceive in the face. The appeal of caricature and grotesque depends upon this kind of emotional response, which their exaggerations then amplify and channel. Such strong feelings! I feel sure that you and I could have a long conversation about this pudgy man with blue, almond eyes and pursed lips! I feel we could tell his story, that he has a fabulous story to be told. Such knowledge and convictions I have—about a melon. A piece of fruit, decorated with simply painted eyes, nose, and a mouth. So powerful is our compulsion to “read” faces and body “language,” and so unshakeable is our belief in this ability, that we are ready to become the soulmate of a melon. We have the proverbial blindness of rutting beasts. (If such a proverb doesn’t exist, it should.) Enjoy this power, I told myself, in art, and beware the insidious insistence of this fantasy elsewhere in the world.

Afterthought

Melon Mask could not have its same effect as anything but a photograph. As a painting or drawing, the same image could not confound, reveal, and deconstruct the theory-laden prejudice of everyday visual cognition; it would rightly be understood as a metaphor or satire, essentially fanciful however serious the intent or trenchant the message: a peasant’s perspective, for instance, which “sees” nobility as fat, corrupt, and profligate. Photography’s special authenticity gives it special access to a critique of objectivity in visual perception, and a corresponding mode of aesthetic play. I often say, after being out and about looking at art in studios, galleries, or museums, that some of the best art I saw was photography, as well as most of the worst.