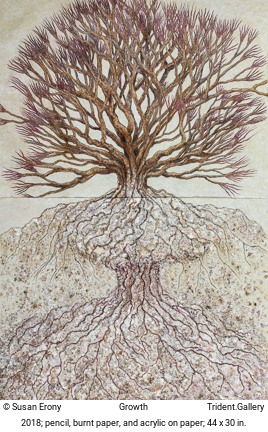

The brilliant nineteenth century American journalist, critic, and women’s rights advocate friends early in life with Emerson and other transcendentalists, and she shared their perception of nature as an expression of divinity.

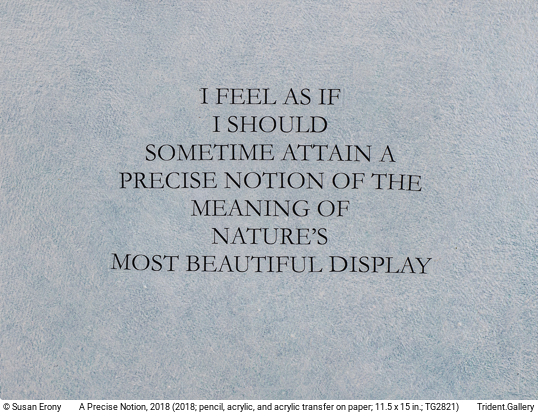

For me, her words describe a state of mind I experience in the presence of natural beauty, a sense that I can never feel or appreciate it enough, see it well enough. I want to understand its beauty and wonder more fully, to incorporate it into my being. I am grateful to Fuller for these words, which both acknowledge a strong desire to know and feel more and calmly accept the feeling of inadequacy, giving more space for emotions of awe and joy.

But there is more about Fuller that draws me to honoring her power, as I try to do by putting her words in public. Fuller became the first editor of the transcendentalist journal The Dial in 1840. Four years later, Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, hired Fuller as a literary critic, and two years later she became the Tribune’s first female editor. She was now earning $500 a year and reviewing American and foreign books, concerts, lectures, and art exhibitions.

She published over 250 columns on art, literature, and political and social issues, such as slavery and women’s rights. In 1845, Greeley published Woman in the Nineteenth Century, her seminal and groundbreaking book on women’s rights, expanded at his encouragement from essays she had published in series in The Dial.

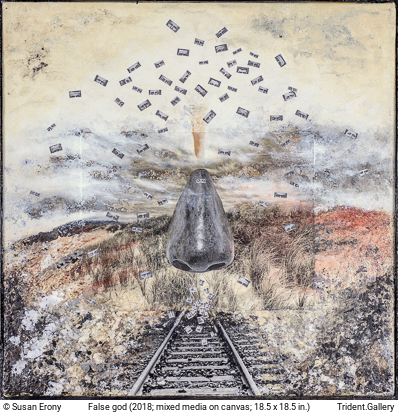

Fuller believed in equality, in the same civil rights for all — for men, for women, and for African Americans and Native Americans, both of whom she believed were wronged by America. She stayed overnight in Sing Sing prison to do interviews and report on an effort to develop a more humane system for female prisoners. She grew concerned with the plight of prostitutes, the homeless, and the poor. She advocated for reform at all levels of society, a concern which separated her from the Transcendentalists, whom she felt too involved with individual improvement and not with societal concerns.

After her book’s publication, the Tribune sent Fuller to Europe as its first female correspondent. In 1846, she met Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian revolutionary in exile in London since 1837, and allied herself with his cause. She also met Giovanni Angelo Ossoli, a Mazzini supporter, who later became her partner and with whom she had a son. Ossoli fought for the establishment of the Roman Republic in 1849, and Fuller volunteered at a hospital and sent dispatches home. The Republican cause went down to defeat, however, and they now had to flee to America.

Upon her return to the US, Fuller planned to finish a book about the history of the Roman Republic. Unfortunately, the family of three all drowned when their American-bound ship wrecked off of Fire Island. They were less than 100 yards from shore, but no one would come out to save them.

Fuller, as one can imagine, was often criticized in her lifetime. She was thought by many to be arrogant. She was certainly radical in her views. She was called “the precursor of the Women’s Rights agitation” by Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage in their book, History of Woman Suffrage.

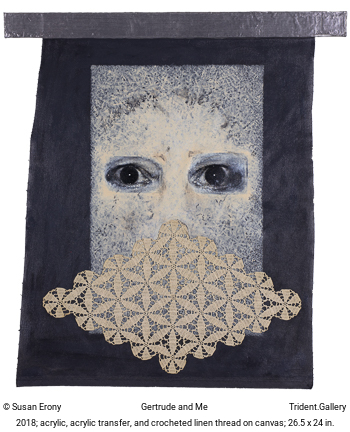

All of the above went into A Precise Notion, 2018. It is still a time when concerns for the rights of women, people of color, the disabled, the poor, the homeless, and concern for civil society deserve the kind of attention and courageous commitment that Fuller gave them, and it is a time when the effects of our thoughtless mistreatment of nature is taking an increasing toll on our lives.

_1000x400px-screen-cap2.jpg)

_1000x400px-screen-cap.jpg)